Migratory birds make some of the world's longest journeys and they face many challenges along the way.

Mighty Migrations

Few birds inspire awe like shorebirds – a group of coastal and wetland-dwelling bird species that perform the longest feats of migration known to the natural world. Also known as waders, some of these species fly the same distance as several round trip journeys to the moon within their lifetimes.

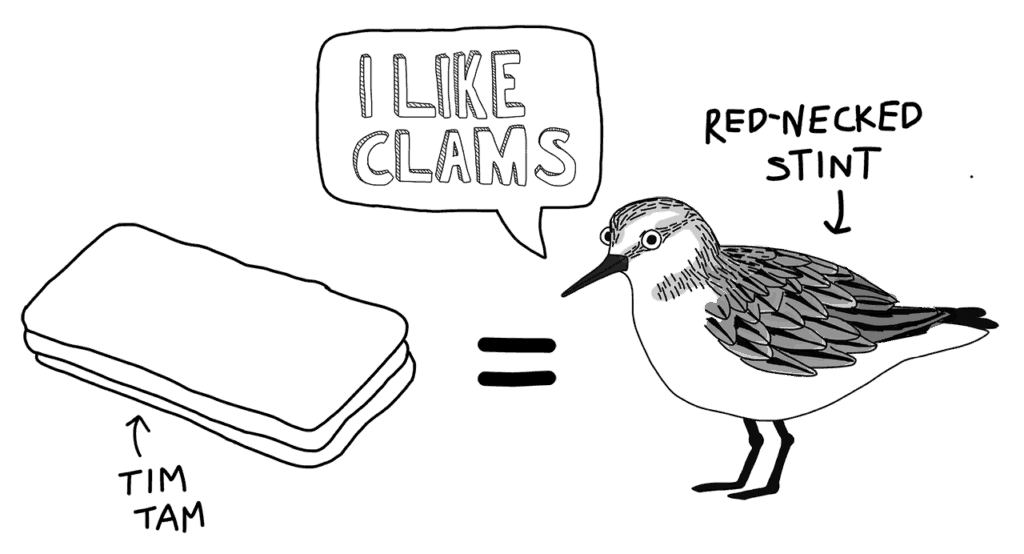

Red-necked stints are the smallest of 36 species of shorebirds that are regular visitors to Australian shores. Weighing about as much as a Tim Tam, a tiny Red-necked Stint can fly up to 3200 kilometres without stopping.

That’s almost the distance from Perth to Melbourne and is just a fragment of its 25,000 kilometre round trip from Australia to Siberia. Such a journey would feel like a once in a lifetime adventure for most humans, but these miniature marvels undertake this epic feat of endurance every year.

Our national highways seem long until they’re compared to the eight international Flyways followed by dozens of migratory bird species annually.

Most migratory shorebirds seen in Australia follow the route known as the East Asian-Australasian Flyway (EAAF), which extends from the Arctic Circle, through northern Russia and Asia down to Australia, passing through 4 continents and 22 countries (see map below).

Northward migration from Australia to breeding grounds on the treeless plains of the Arctic tundra typically occurs during March or April. The birds arrive in time to nest during a short window in the Northern summer months when their young can take advantage of an abundance of insects. They make the return journey to ‘over-winter’ from July to October at non-breeding grounds in Australia – the southernmost feeding destination of the EAAF.

Every great road trip requires many snacks, but shorebirds take binge eating to the next level.

Shorebird migrations are a product of metabolism. To obtain enough energy to propel themselves across vast landscapes and oceans, migratory shorebirds rely on foraging and gorging over several months to build up vital stores of fat and protein.

As these energy stores are depleted during flight, the birds need to stop and feed at invertebrate-rich wetlands and tidal mudflats known as ‘staging sites’. Without these crucial refueling stations, these travelers lack the energy required to complete their journeys and fail to reproduce.

"...shorebirds take binge eating to the next level."

Dangers and Degradation

Of the eight major global Flyways, shorebirds in the EAAF are the most highly threatened, experiencing species decline rates of up to 8% per year – among the highest for any ecological system on the planet.

In the 2016 IUCN Red List update, seven shorebird species endemic to the EAAF received elevated conservation status. Both the Eastern Curlew and Curlew Sandpiper were upgraded from endangered to critically endangered due to population decreases of 80% in the last 30 years. Without intervention, species like the Curlew Sandpiper are predicted to face extinction within the next decade.

Calidris ferruginea

Numenius madagascariensis

Tidal flats around the Yellow Sea in China, Korea and Taiwan are vital for the survival of many shorebird species. About 2 millions birds, or 40% of the shorebird population using the Flyway, rely on this crucial resource to refuel before the last stretch of their northward migration. Unfortunately, almost 50% of tidal areas in this region have been destroyed in the last 50 years through land reclamation for agriculture, aquaculture and industry. Likewise, incremental loss of wetland habitats in Australia is inflicting a ‘death by a thousand cuts’ effect, further contributing to declining shorebird numbers.

Due to their movements through both developed and developing nations, migratory shorebirds represent one of the biggest biodiversity challenges in the world. Their ongoing survival is dependent on complex international relations to coordinate strategic conservation efforts to ensure preservation of key habitats in Australia and overseas. Scientists say that increased monitoring is a crucial first step for improved conservation.

Citizens Stepping Up

While conservation may seem like a scientist’s dilemma, everybody can play a valuable role in contributing to shorebird survival. Understanding the migratory ecology of shorebird species is essential to developing effective conservation and management strategies.

To obtain data on migratory movements, breeding success and lifespan, The Australasian Wader Studies Group (AWSG) and other regional shorebird groups rely on volunteers to assist with the capture, banding and flagging of shorebirds so that researchers can identify and track individuals over time.

BirdLife Australia’s Shorebirds 2020 program also relies on citizen scientists to conduct annual summer and winter shorebird counts at 150 key stopover sites across the country. These counts provide ongoing monitoring of changes in shorebird population sizes and have been used by governments and policy makers to inform conservation decisions.

Volunteers of all levels, from beginners to lifelong birders, make huge contributions by participating in activities run by these organisations. Visit the BirdLife Australia website for more information about how to get involved.