Shorebirds are so-called because most of them live within the tiny strip between land and water called the shore.

If you consider how much of the Earth’s surface is covered by ocean and how much is covered by land, the proportion occupied by the half watery-half terrestrial realm of a typical shorebird really is tiny by contrast! Combined with their habit of gathering into big flocks, this means that many hungry mouths must be fed by a very small amount of habitat.

An amazing range of bills

Through evolution, shorebirds have dealt with the problem of hard-to-find prey through differences in bill structure. Look at a flock of shorebirds on a mudflat and you are likely to see a number of species. The most distinctive feature of each species will usually be the shape of its bill.

A shorebird’s bill is the tool of its feeding trade. Just like a plumber might need a wrench to fix a leaking pipe, or a carpenter needs a saw to cut through wood, the bill of each species of shorebird is specialised for a specific feeding strategy.

Bar-tailed Godwits and Far Eastern Curlews have exceptionally long bills. These are able to probe deep into soft mud and capture food items buried far below the surface.

The long bill of Eastern Curlew (top) and Bar-tailed Godwit (bottom) are perfect for probing deep into the soft mud of a mudflat in search of buried food.

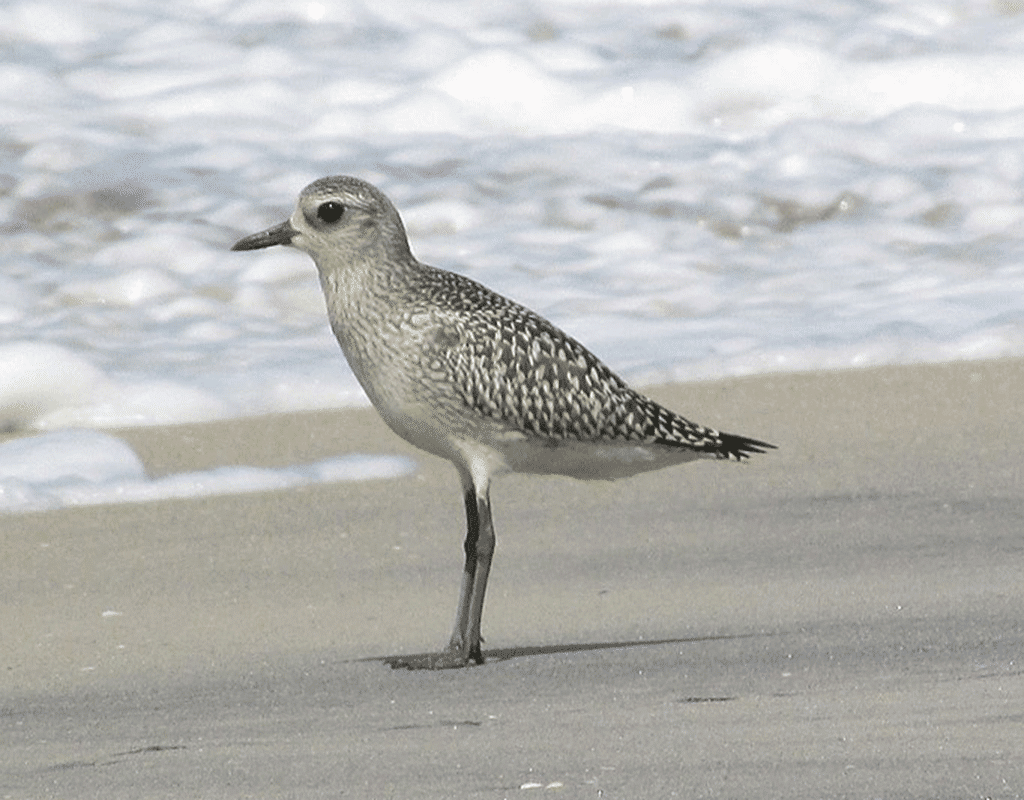

On the other hand, species like the Greater Sand Plover and Ruddy Turnstone have shorter bills that they use for snatching prey from the surface or probing among seaweed and rocks on the beach.

The Greater Sand Plover (left) and the Ruddy Turnstone (right) wield short bills to snatch prey items from the surface of the shoreline.

As well as differences in length, the curvature of the bill also differs between species. From the strongly down-curved bill of the Curlew Sandpiper, to the straight bill of the Grey-tailed Tattler, to the slightly up-curved bill of the Terek Sandpiper, each unique bill allows its owner to catch and eat a different types of food resources to its neighbours.

Together, these differences help to ensure that each species has access to a particular type of prey and reduces the level of competition between species.

A flexi-bill?!

Although a shorebird’s bill may look hard and rigid, looks can be deceiving. Many species of shorebirds have a flexible bill tip which they can move below the surface of the mud to grab food items such as clams, annelid worms, and crustaceans.

Murky water and thick mud mean a shorebird probing a mudflat for food is rarely able to actually see its prey. Instead, the bills of many longer-billed species are packed with tiny pits containing touch-sensitive nerve endings called Herbst’s corpuscles. These allow a feeding shorebird to find food by feel alone.

By contrast, shorter-billed species like plovers have large eyes because they feed using sight on the surface.

Species that catch most of their food on the surface, such as the Grey and Pacific Golden Plovers, typically have short bills and large eyes.

The cost of bills

Although a shorebird’s bill is undoubtedly an irreplaceable tool, it does come at a cost. Underneath the outside of the bill is a network of blood vessels. These can help the bird lose heat if it becomes too hot but may also result in too much heat loss if it is looking for food in cool, wet mud.

Losing too much heat isn’t ideal and a shorebird may need to limit heat loss in cool environments. This is one of the main reasons that shorebirds often roost with their bill tucked away under a wing because it helps them to stay warm.

Another way that bill shape can prove costly to shorebirds is if their environment changes around them, leaving their specialised bill badly suited to capturing what food is currently available.

Climate change may be having a negative impact on shorebird bill development. Warmer spring temperatures in their Arctic breeding grounds are causing insects (the primary food source for newly-hatched shorebirds) to reach high numbers earlier in the season before most of the shorebirds’ eggs have hatched. This means that there is less food around for the chicks and they are not able to eat as much food as they need to fully develop their bills as they grow up.

Because of this, some young shorebirds now have smaller bills, leaving them unable to reach prey that is buried deep in the ground. This means that fewer are surviving to adulthood.

Use your incredi-bill knowledge to identify shorebirds!

The amazing diversity in shorebird bills is one of the key reasons for their success. It enables these birds to feed on different kinds of prey and in different habitats. However, having a unique bill may also leave them vulnerable to change.

Next time you are lucky enough to be watching a flock of shorebirds, make sure you take the time to marvel at their highly specialised bills. Not only is a shorebird’s bill a handy feature to help you spot a particular species, it will also provide you with insight into how each species interacts with its environment. They really are incredi-bill!