Introduction

by Clive Minton & Grace Maglio

One of the tagged birds with leg flag ID, SEP, made its way from the coastal plains of Eighty Mile Beach to the backwaters of the Almatti Dam in Karnataka, India.

Upon hearing the news of the bird’s arrival in India, a surveying team was subsequently organised and the expedition “In Search of SEP” began.

We have just received this comprehensive report from Subbu Subramanya detailing the team’s huge efforts to find SEP and their success. It gives a brilliant account of observations in this area and the potential conservation implications.

Collaboration & teamwork

by Subbu Subramanya

It was the message from Nita Shah from the Bombay Natural History Society, Mumbai, asking for assistance from birders in Karnataka to assist in tracking the Oriental Pratincole, SEP that had been fitted with a PTT (platform transmitter terminal) by the Australasian Wader Studies Group (AWSG) and Tern Expedition Team at Northwest Australia, that set the ball rolling. Taej Mundkur – Senior Technical Officer, Wetlands International – reiterated how important it is that the bird be found and put me in touch with Clive Minton for the details on daily satellite feeds on Oriental Pratincole in Karnatka.

Grace Maglio provided the details on the location of SEP, which appeared to have made a large Central Island in the backwaters of Almatti Dam near Heggur village in Bagalakot, in North Karnataka its summer home.

Almatti Dam is a hydroelectric project on the Krishna River in North Karnataka, India. It was completed in July 2005 and it is located on the borders of Bijapur and Bagalkot districts of Karnataka. Being a Hydro-electric project for generation of 290 MW power, the reservoir with a total water spread area of 487.87km2. is off-limits to public and one requires official permission for movement within the reservoir area and to access the 22km2 island in the middle of its backwaters.

Thus, I approached the Karnataka State Forest Department (KSFD), specifically, Mr. Subhash Malkhede, Additional Chief Conservator of Forest (Wildlife), as the very search and locating of SEP fell within the preview of the Central Asian Flyway National Action Plan, for which, KSFD is a Nodal Agency to implement the action plan across the seven southern Indian states. As an initiative of cooperation between countries coming under two Flyways namely, East Asian –Australasian and the Central Asian Flyways, Subhash Malkhede, directed Mr. P.K. Naik – Deputy Conservator of Forests – at Almatti to provide me with necessary logistical support to look for SEP. Mr. Naik enlisted the support of Dr. Kumar Desai, the Honorary Wildlife Warden, Bagalkot, to accompany me along with several of his KSFD staff stationed both at Bagalkot and Bijapur towns.

On May 12th, I reached Bagalkot from Bangalore and soon I was accompanied by the Forest Department staff and Dr. Desai, to reach the Central Island at Almatti. Details provided by Grace showed that SEP had reached the Central Island on April 22nd and was still present on May 5th.

A boat was pressed into service, and we all landed on the island and made our way through a deciduous scrub forest dominated by Acacia nilotica and invasive Prosopis juiflora (Figure 1.), on the central spine of the island that stretched for about 5km and all the locations of SEP provided by Grace were to the north of this

P. juliflora forest.

No sooner we emerged out of the forest, at around 12.30pm, we could sight Oriental Pratincoles (OPs) flying about and very soon, we found a few birds performing broken-wing display (Figures 2. & 3.), indicating that the birds were already breeding.

Soon, we located at least 5 nests of OPs and the and four of them contained 3 eggs each and one with two eggs (Figure 4a.). As we felt it was unethical to disturb the nesting process, we moved away from the nests after taking a few quick photographs and stopped looking for nests. We also had to pick our way, in an effort not step over OP nests. As we felt it was unethical to disturb the nesting process, we moved away from the nests after taking a few quick photographs and stopped looking for nests.

Figure 4a. Nests of Oriental Pratincoles with eggs at the Central Island of Almatti backwaters.

In an effort to locate SEP, we started scanning every flying OP, for the tell-tale PTT antenna that would be protruding beyond its tail. We also tried to look for the yellow leg-tag among the birds that were standing on the ground. In the next two hours, we surveyed about 4km2 of the island area, between the shoreline and the forest edge, but with no avail, as none of nearly 100 birds that we observed carried neither the leg- tag or the PTT antenna. In this 4km2 stretch, we counted around 25 nests being incubated. We returned after spending about three hours on the Island, in the afternoon, to get away from the searing heat of the day.

Next day, we decided to visit another area of the backwaters called Herkal, about 10km due south of the Central Island, where the Forest Department staff had seen a large number of OPs. This area is on the mainland shoreline of the backwaters. The area is being intensively cultivated, all along the edge of backwaters with dryland crops like Maize (Zea mays), Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) and Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea) by a large number of farmers to exploit the residual moisture in the soil, as the waters of the backwaters receded slowly.

The OPs were all over Herkal area, found in plots that were freshly ploughed, with a week to month old crop seedlings (Figure 6.), in addition to interspersed patches of fallow, uncultivated plots, that were overgrown with grass and weeds. This area held much higher densities of OPs than the Central island. In the 4km2 area that we surveyed, we must have seen close to 500 OPs.

While we observed the birds, we did not make any effort to locate nests, although, almost every bird that we observed was performing broken-wing display, indicating that they were nesting and we were close to their nests. We did not see any freshly fledged nestlings, indicating the nesting activity of OPs was quite synchronous. While we surveyed the area, we literally picked our way, in an effort not to trample on any nests. Also, we did not find any birds carrying food in their beaks, indicating that most of the OPs had eggs in their nests.

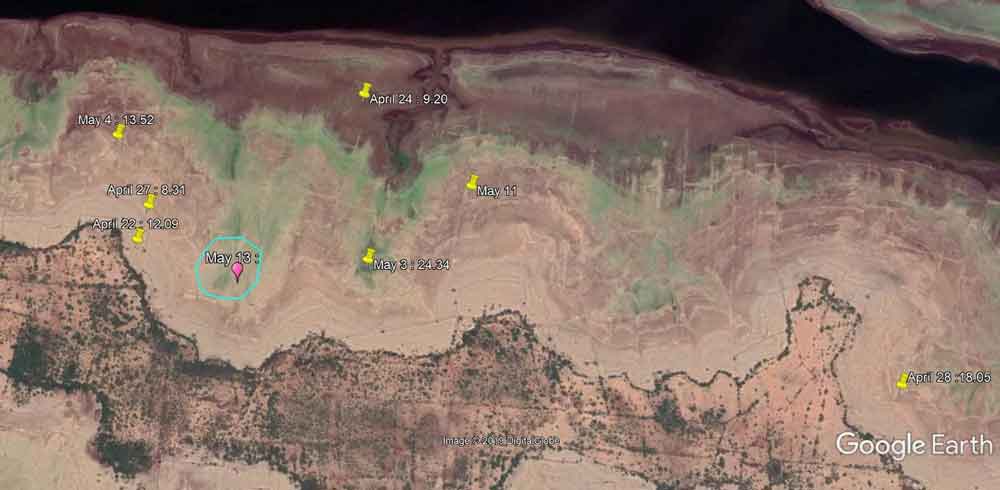

On May 12th, Grace sent details of a fresh satellite feed on SEP’s location obtained on the previous day, which was very close to the location where we had surveyed the Central Island on May 11th (Figures 8a. & b.). Based on this, we decided to try survey the Central Island one more time.

On May 13th, I started from the Almatti Dam along with a Forest Guard at 6.30am and the boat ride took about an hour to arrive at the shores of Central Island, close to the location where the position of SEP had been picked-up by the satellite on April 28th. Initially, I came across a nesting area of some 50 Small Pratincoles (Glareola lactea), which were performing broken-wing display and no active nests could be found (Figure 9.).

As we headed towards the location where SEP was recorded on April 22nd, OPs were more commonly seen. The OPs were flying overhead, screaming as they flew about and many were seen performing broken-wing display, which reminded us to pick our path carefully. I made it a point to look at every OP on the ground with my spotting scope and did not fail to watch almost every OP that was flying, looking at the tip of the tail for the PTT antenna.

At 10.05, when I observed an OP in flight with my field glasses, my heart skipped a beat, as I could see the long PTT antenna projecting beyond the tail. As the bird prepared to land on the ground, I pointed-out the bird to the Forest Guard who had accompanied me, and asked him not to let the bird out of his sight even for a few seconds. My hands shook, as I took the first photographs and they were all hazy. I emailed Grace at 10.13 (IST): “FOUND YOUR BIRD!!! Have a hazy image showing the leg tag”. The bird presented me with more opportunities later, to photograph it and at 10.30am it mingled with a few other flying OPs and moved away and could not be located again (Figures 10. & 11.).

Nature of the nesting habitat

At the Central Island, the OPs preferably nested well away from the water’s edge and appears to select patches of land that were quite dry and the grass had started to dry (Figure 12.). In keeping with its Latin name of the genus Glarea, meaning “gravel”, referring to its typical nesting habitat, the OPs nested in bare gravelly ground with patches of dry grass and other weeds (Figures 13. & 14.).

In the Herkal area, OPs used fallow land covered with grass, weeds and gravel in addition to cultivated fields. The high densities of OPs that were found at Herkal could possibly be due to dry cultivations, that could provide greater feeding opportunities, than what was seen on the grassy margins of the backwaters at the Central Island.

Threat to nesting Pratincoles at Almatti backwaters

The presence of feral horses and cattle and about 500 sheep and goats that were present on the Central Island are expected to pose considerable threat to the nesting of OPs (Figures 18a. & b.). These livestock could potentially trample the nesting area and damage nests and their contents. Sheep grazing was seen at Herkal area as well (Figure 19.).

Other than these, no other predators were observed at both the sites visited. Being the end of migratory period, none of the birds of prey were seen and most of the migratory raptors appeared to have left the backwaters. Even the resident predatory Brahminy Kite was not encountered in the two areas.

Way Forward

The sighting of SEP has generated quite an interest and the State Forest Department has shown keen interest in protecting Almatti Backwaters to conserve both resident and migratory waterbirds. It is planning to get the area declared as a wetland of national importance and plans even to apply for the Ramsar Site tag. As a part of this initiative, I am planning to push for the Central Island to be declared as a Conservation Reserve, for protecting OPs. Future days will reveal how these plans will take shape.

Acknowledgements

Clive Minton

The extensive and expensive satellite tracking program we have set up in NWA has only been possible through the efforts and generosity of a large number of people and organizations. It is difficult to know where to start with the formal acknowledgements so I will list them – but not in any particular order of priority.

- The members of the AWSG NWA 2019 Wader and Tern Expedition and similar NWA expeditions in previous years, are particularly thanked for their efforts in the field in catching, banding and deploying transmitters on a range of species.

- Landowners are especially thanked for permission to go onto their property to enable us to catch various species in order to deploy the satellite transmitters. In particular we thank Anna Plains Station for giving us the freedom to roam over large areas of grazed grassland when counting and catching target species.

- AWSG acknowledges the Yawuru People via the offices of Nyamba Buru Yawuru Limited for permission to catch birds on the shores of Roebuck Bay, traditional lands of the Yawuru people.

- AWSG acknowledges the Karajarri and Nyangumarta people for permission to catch birds to be marked for this project on the shores of 80 Mile Beach, traditional lands of the Karajarri and Nyangumarta.

- The cost of the satellite transmitters, which cost around $5000 each, and the satellite downloading costs (around $1000-1500 per month) have been met by a variety of sources. Private individuals (Charles Allen and Doris Graham) have made most generous individual contributions. Kate Gorringe-Smith and her team of artists involved in The Overwintering Project made a large, generous donation from funds raised during their various public exhibitions. The annual NWA Expedition members, collectively, also provided significant funds each year.